“For their sakes, show the world that people like you and they can be quite as selfless and fine as the rest of mankind. Let your life go to prove this — it would be a really great life-work, Stephen.”

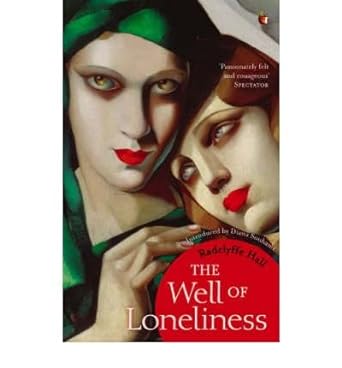

Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness is regarded as part of the sapphic canon — an international bestseller, a seminal work of gay fiction and the predecessor of lesbian pulp fiction.

Despite the fact that the book is not sexually explicit, it became the subject of an obscenity trial in the UK upon publication in 1928, resulting in an order that all copies of the book be destroyed. (That alone is reason enough to wade through it, in my opinion.)

As Stephen King famously said, we need to go and find the banned books, the censored books. Find out what it is they’re so desperate to keep from us.

Fortunately for us all, Radclyffe’s novel survived the controversy and, for decades, was regarded as the most renowned work of lesbian literature.

Stephen Gordon is is the epitome of an ideal child born to aristocratic parents — a skilled fencer, a keen horse rider, and an able scholar. In youth, Stephen becomes a war hero and a celebrated writer. But… Stephen, named after the boy her parents wanted, is a woman. An “invert”, in her own words. And the novel, quite simply, is the story of her struggle.

Given the title, perhaps it goes without saying that this book is neither an easy or uplifting read. Virginia Woolf commented, “the dullness of the book is such that any indecency may lurk there — one simply can’t keep one’s eyes on the page”.

Did I enjoy reading it? No. Am I glad I have read it? Absolutely.

It isn’t, of course, a read that fits with modern sensibilities. But it is, I would argue, essential reading. It’s part of sapphic history — a courageous and important cultural artefact that paints a vulnerable, sympathetic portrayal of lesbians and bears crucial witness to attitudes of the time.

In spite of its critical reception and legal troubles, The Well of Loneliness did what all great books do — it reached people and gave them words of comfort and understanding.

Puddle, Stephen’s governess, puts it best:

“You’re neither unnatural, nor abominable, nor mad; you’re as much a part of what people call nature as anyone else; only you’re unexplained as yet — you’ve not got your niche in creation. But some day that will come, and meanwhile don’t shrink from yourself, but face yourself calmly and bravely. Have courage; do the best you can with your burden. But above all be honourable. Cling to your honour for the sake of those others who share the same burden. For their sakes show the world that people like you and they can be quite as selfless and fine as the rest of mankind. Let your life go to prove this — it would be a really great life-work, Stephen.”

And wasn’t it just. The Guardian reports that Radclyffe Hall received thousands of letters of support. In one such letter, a married coal miner from Doncaster writes to the novelist that he is dismayed by the bigotry of so-called ‘thinking men’. “Some day,” he says, “we will wake up, and demand to know ourselves as we profess to know about everything else”.

We live in hope.